The Expanding Universe of Unbelief

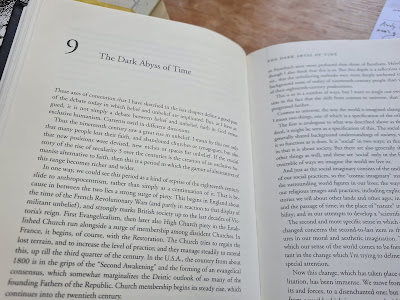

The Chapter 10 of A Secular Age is about the nineteenth-century, and the expansion of unbelief across the period. If unbelief starts to spread, moves from a social impossibility towards something more normative, in the eighteenth century it accelerates and expands markedly in the nineteenth. Why? Or more to the point: how? Taylor says ‘when medieval poets write about angels, they partake of a particular sacred hierarchy, a placement and position in a divinely ordered cosmos.’ When Rilke writes about angels, ‘they cannot be understood by their place in the traditionally defined order.’ We ‘cannot get at them through a medieval treatise on the ranks of cherubim and seraphim, but we have to pass through this articulation of Rilke's sensibility’ [353]. What changed? We could describe the change in this way: where formerly poetic language could rely on certain publicly available orders of meaning, it now has to consist in a language of articulated sensibility. Earl Wasserman has shown...